Orwell and Decency

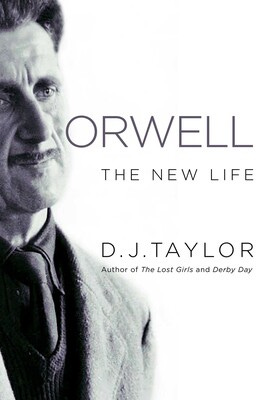

An Essay Occasioned by D. J. Taylor’s Orwell: The New Life (Pegasus Books, 2023)

George Orwell knew the historical tribulations of the twentieth century firsthand: colonialism in Burma, the agony of the Spanish Civil War coupled with the lies and manipulations of the Stalinist “allies” of the Republicans, the rain of bombs that was the London Blitz, the struggles of the poor in France and England to make ends meet, and the authoritarian power of ideology to reduce people to nothing and less than nothing. It is fair to ask then what sustained him in his endless labors as a writer and as a political being. The modest answer (a friend of his once called Orwell “modest, gentle, and angry”) was one that especially suited him as someone who spurned the siren of progress-at-whatever-cost—human decency.

That quality seems, at first glance, to be a thin pennant to fly in the face of the fierce winds of power. As a quality, it resists definition. Typically, we cite decency along with an example: “She did the right thing.” Appropriateness is involved but much more than good manners is being attested to. Orwell was irreligious and never would have traced such decency to a spiritual proclivity. Religion, for him, led to humbug; its posturing about higher matters did not so much promote decency as impede it. Nor would he have traced it to the so-called principles that dominated English public schools. As an Eton graduate, he knew such schools and, though he appreciated aspects of his education, he had no use for the class-ridden air of self-congratulation. Any ruling class, since ruling encouraged conceit and curtailed empathy, was purblind, to say nothing of wicked.

Decency spoke to human dignity, not as a series of credos and rules but as an active force, something in people that amounted to a personal code of conduct but one that did not require explanations or negotiations. Decency had a large part to play in mutuality, in helping people to live together in a peaceable way. Unlike so much in the assertive, propagandizing modern world, decency had no need to call attention to itself. It was not news in the sense of the terrible eventfulness of wars nor in the scripted blather of what passed for importance. Decency was old-fashioned in a literal sense—a feeling for the old ways of people relating to one another and was almost a folkway in that regard. The stirring up of everything in modern times could also be seen as an unraveling. His distrust of great promises marked Orwell as a social conservative.

Nation-states and corporations are, for all their protestations, inherently indecent, preferring policy and profit to the exclusion of other ends and means. Moral feeling has never been on the top of their list. Whatever shows they have made of decency have been exactly that—window-dressing to justify whatever expediency presented itself. The brutalities of Nazism and corporate imperialism were hardly a surprise. Nazi decency pertained to removing soldiers from extermination squads because mass killing upset them. Imperialist decency pertained to after-the-murderous-fact philanthropy and missionary efforts. Using up African and Asian lives was a by-product, something not to be thought twice about.

Part of the gist of the totalitarian state was to destroy decency, to make spies of everyone, to prey upon human weakness in the name of some shibboleth. Such states were bound to destroy settled ways of being—peasant culture, religion, traditional artistic endeavors—in the name of various leaps forward. Orwell opposed this with every fiber of his being and instinctively looked hither and yon for support. One place he found it was in the works of Charles Dickens, the subject of a long essay and an exemplar of sorts for Orwell. It is worth quoting this passage at length from Taylor about Orwell and Dickens:

“The author of Hard Times, criticized at the time of its publication for peddling ‘sullen Socialism,’ is, we discover twenty thousand words later, neither a Marxist, nor a Catholic, or even an orthodox nineteenth-century liberal. In fact, he is not really anything except a supremely adroit humorist and a man who believes that the world will be a better place if we all behave better. Change cannot be prescribed: it has to come from within. Dickens’s great virtue is that he is a free intelligence and therefore loathed with a vengeance by [in Orwell’s words] ‘all the smelly little orthodoxies that are now contending for our souls.’”

“Free intelligence” is not a common commodity, particularly when linked with the possibility that is available to any of us to behave better. Such behavior has no savor of sanctimonious certainty. Decency is an instinct that wants to be encouraged but inquiry is also an instinct—all children have it—that wants to be encouraged. The best way to actually speak to the benefits of civilization, an entity clearly outside of political locales thus far in the human pageant, is to speak against civilization, to challenge the presuppositions and keep people honest. The belief any group has in the value of its particular brand of civilization is very partial. Orwell, accordingly, loathed apologists of every stripe. The work to be done, as a writer and person, was not only to issue challenges that were practicable and honest but to appreciate, as in the Dickens essay and many others by Orwell, the value of whatever was under consideration.

The discounting of value in modern times as irredeemably subjective has debilitated people and left them embracing monoliths—ideology, money, and technology, to name three—that do not go very far in helping us to live constructively with one another and with the earth. Big Brother, to reference a brilliant fictional notion of Orwell’s, does not know and will never know, however much Big Brother believes he knows everything and will destroy you in order to prove that. The voice of decency in Orwell never gave in. You can call him stubborn, obsessed, and angry, but you can also call him courageous.