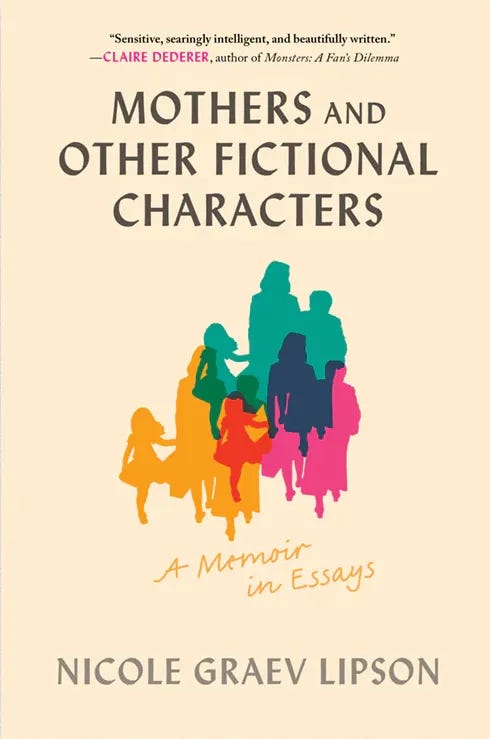

Nicole Graev Lipson is the author of the memoir-in-essays Mothers and Other Fictional Characters (March 2025); an essay from this book, “As They Like It” was reprinted in The Best American Essays 2024. Her essays and criticism have appeared in Virginia Quarterly Review, The Sun, The Gettysburg Review, River Teeth, Fourth Genre, The Millions, The Washington Post, and The Boston Globe, among other publications. She is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize, and her work has been nominated for a National Magazine Award. Lipson received her MFA from Emerson College and lives outside of Boston with her family.

Listen to Nicole Graev Lipson read the first three minutes of “As They Like It” (in Mothers and Other Fictional Characters), originally published in the Virginia Quarterly Review and reprinted in The Best American Essays 2024.

Interview

BY: The title of the collection, Mothers and Other Fictional Characters, was so intriguing to me. What does it mean to you for a mother to be a fictional character, as the title implies? And where did the idea for the title come from?

NL: I think it's an experience that many women, many humans, have had where there's a schism between who they are when they step out into the world, and who they feel themselves to be internally. For me, personally, that schism was most intense in my life after I became a mother. There was something about that particular identity that the schism felt even more heightened than it had before. I found myself losing myself to that kind of mythical, fictional identity of what makes a mother, what a good mother should be, some of the performative trappings of motherhood. There's a lot of costumery and pageantry involved in mothering. A lot of performance. Adrienne Rich distinguishes in Of Woman Born between motherhood as an institution and motherhood as an undertaking, an act, an orientation to the world. When I talk about mothers as fictional characters, I'm really talking about motherhood as institution and the ways that it asks us as women to perform fictional versions of ourselves.

As I ventured further into the writing of the book, I really started to see that even though this investigation began with my thinking about motherhood as a performance, that motherhood was just one of a series of performances that are asked of women over the course of the female lifespan. I really started to think about the multiple fictional characters that I have embodied. It is a memoir, so I'm writing from personal perspective, starting in girlhood, moving onward through young adulthood, adolescence and young adulthood into motherhood, and then looking beyond. I'm in my forties now, standing in the shallows of middle age and looking ahead to the rest of my life. Who are those fictional characters before me? Is it the fictional character of the Crone? Is it a descent into invisibility, which accompanies so many women in our culture as they grow older? I was really interested in that blurry line between truth and fiction in women's lives, and also the ways that we as women can become complicit in telling these stories.

I always like in my work to interrogate how we can both look critically at our culture, but how we are also of our culture, and how it is inside of us. We do not stand separate from it, we embody it and we live it.

For many years, I have thought a lot about the ways in which fictional characters—for the sake of my book, I'll say fictional women—can be more true than the real women who are performing a scripted version of womanhood. Literature, because it allows us a window into the layered and multi-dimensional complexity of its characters, allows us to see truth in a different way. I'm seeing into [fictional characters’] psyche in a way that I'm not seeing into the psyche of the fellow mother who I passed in the hallway on the way to drop my kid at preschool. I can create all kinds of fictions around her. She can present, you know, a fictional self in the world of what she is as a mother. I'll never know. Ironically, you know the place where I have found truth—and where so many people find truth—is in literature.

BY: Most of the essays in the collection were previously published in various periodicals, over the course of a few years. I believe the only ones that weren’t are “Witch Lineage,” “The Friendship Plot,” and “Memento Mori.” I’m really curious about how the collection came together. When did you decide to publish your essays as a collection? Was it something that you had wanted to do from the beginning of writing them, or did you realize somewhere along the way that you had the makings of a fantastic memoir spread across many magazines?

NL: When I began writing this book, I didn't know that I was writing a book. The book began a number of years ago when I began to write some essays in the earlier stages of motherhood about my experiences. Some things that I was ruminating about, thinking about, confused about, and I'd written around three of these when I began sending them out, getting them published in literary journals. These early ones are earlier in the book. On the surface, these essays were about quite different things. The opening essay is about my mother's affair and my own extra marital longings (twenty or fifteen years at that point) into an otherwise happy, stable marriage. “The New Pretty” was about beauty standards for women, and thinking about the ways that we can pass on ideas about female beauty through generations. On the surface these were different, but I began to realize that they were all circling around this more central theme of the blurry boundary between truth and fiction in women's lives, and how we really so often find ourselves straddling these two realms as we move through the world. Once I realized that, I remember this sort of flutter of excitement from seeing how I could pursue this line of inquiry over the course of a book.

I think it was then too that I realized that the scope was larger than motherhood. I started to the envision the book as moving through archetypal stages of a woman's life. From girlhood to maidenhood to motherhood, if one becomes a mother.

“I love how truth grounds me. Not to say that you can't bring the tools of fiction into nonfiction writing. I definitely feel that I do that in terms of world building and scene and dialogue and character development. But for me, the benchmarks of truth and memory are really important.”

BY: I’m curious, for all your talk about fiction, if you've written fiction extensively at all?

NL: No, no, no, I'm terrified of fiction.

BY: Why are you terrified of fiction?

NL: I need the structure and direction of truth in my writing. The idea of writing fiction, to me, is like standing in the middle of an open field with just horizon on all on all sides, no limits. It gives me this kind of panicky feeling, as if I have agoraphobia. Yeah, there's just too many directions you could go in, nothing confining me, nothing guiding my way. One of my closest friends in the world is a novelist, and I marvel at her and what she does every day. I have so much respect and admiration for fiction writers, but I'm not one myself.

I love how truth grounds me. Not to say that you can't bring the tools of fiction into nonfiction writing. I definitely feel that I do that in terms of world building and scene and dialogue and character development. But for me, the benchmarks of truth and memory are really important.

BY: Your essay “As They Like It” has a lot of homes for an essay. It originally appeared in the Virginia Quarterly Review in 2023, then in Best American Essays 2024, and finally in the collection this year. Did you anticipate the essay having such an immense positive reception? How has it felt for this essay to succeed so wildly?

NL: I did not anticipate the essay having an immense positive reception. But, receiving the email that the essay had been selected for The Best American Essays was truly one of the best moments of my life. It's exciting to know that any essay is chosen for The Best American Essays. It’s such an honor. But for this essay in particular, which had felt so risky to me and which I really did not know how it would be received? For it to receive that recognition was just deeply meaningful for me personally.

BY: What were you doing when you got the email? What was happening? What did it feel like?

NL: So if anyone reading this is a parent, you know that the worst, most busy time of the day is five o'clock. The kids are home and you’re trying to get the homework done, trying to get dinner on the table. I still haven't wrapped up all of my work for the day. I still have unanswered emails, something is on the pan in the kitchen. I remember taking a moment to sit down. I think I had some unanswered emails to respond to. I remember sitting down on my couch in our little family room that's near the kitchen, and opening my email and just seeing the headline. And I just shrieked. I just gasped, covered my mouth with my hands, shrieked, and my kids came running over. It was pretty amazing. It was a dream come true.

I've read The Best American Essays for years and years and years. I actually wrote an essay my senior year in college that my professor encouraged me to submit to literary magazines. I didn't even know what literary magazines were at that point. I remember going to the stacks of the Cornell library and reading literary magazines, buying a big copy of the Writers’ Marketplace, which used to be this big book that, before the internet, you would pour over to figure out where to submit. I submitted my essay by mail to a number of literary magazines. That essay ended up being published in The Hudson Review, which is a wonderful literary magazine that's still around, and selected as a notable in The Best American Essays. That was twenty-five years ago. It's been a long journey for me.

“All of my essays start from a place of confusion. It's always some sort of confusion that draws me to the page, that makes me want to write. That's what I'm compelled by, love and confusion.”

BY: “As They Like it,” which is about learning to understand your child’s gender nonconformity, tackles some sensitive material in an incredibly honest way. One of the most compelling parts of the essay for me was the immense vulnerability it must have taken to write and publish it. As you yourself note in the essay, you’re hesitant about publicly giving voice to some of your thoughts. Can you tell me more about how it felt to write such a vulnerable essay?

NL: I didn't know if I was going to try to publish this essay when I started writing it. Usually, I know from the beginning if I feel like the essay is going somewhere, but the whole time I was writing that essay, I didn't know whether I was going to pursue publishing it. There's a well-known adage in the writing world, to write what scares you. I feel that I took that a step further with this essay, which is to say I was writing what absolutely terrified me to write about. The prospect of putting it out in the world literally made me shaky and nauseous with fear. The essay is about what it's been like for me as a mother to observe my oldest child migrating away from the identity of a girl toward the identity of a boy. As I watched, as I was experiencing this as a mother, there were aspects of it that were confusing, right? All of my essays start from a place of confusion. It's always some sort of confusion that draws me to the page, that makes me want to write. That's what I'm compelled by, love and confusion.

On the one hand, I love my child more than words can encompass, and wanted them to know that I supported them wherever this journey was headed. And on the other hand, this was a totally new experience for me. There were things as a parent that I've become seasoned at dealing with, right? I have three children, and you learn as you go. We don't come into this world as parents fully formed. We become parents in the doing. But I had never parented a gender nonconforming child before. Always as a reader I’m looking for companionship. Looking for answers. Looking for the feeling that I'm not alone by looking for something to read by someone who's been through something similar, and might be experiencing some of the same things. I was hungry for the stories of other parents who had felt some confusion or ambivalence or uncertainty or feeling of being a fish out of water when they started to observe their child migrating toward a different gender identity. But I couldn't find pieces like that. All of the pieces that I could find by parents of gender nonconforming or trans children were nearly all persuasive in their rhetorical mode. They were op-ed pieces in the service of a politicized stance.

These op-eds aligned really neatly to certain orthodoxies, right? These very polarized views. And I couldn't find much in the in-between. I started to write about it almost, out of the gift of desperation. I wasn't finding kindred spirits in my reading. I started writing that essay as a small gesture toward trying to find kindred spirits through my writing. At the time that I was writing that piece, the issue of kids and gender was so polarized that to question anything or to show any confusion or any doubt felt to me like putting myself at risk. Gender in kids is one of these issues, but I think that there's a number of them in our culture where being of two minds, or being of multiple minds, can be met by some people as an act of violence to their side. But I don't think that we as a culture should forfeit complex, contradictory, nuanced, messy thinking in the name of activism, no matter how well meaning. I think that actually doing so is a really grave mistake. It only makes the other, I'm putting this in air quotes, “side” dig in deeper. I don't think it's constructive to really understanding or fostering dialog.

The essay is a place for confusion. More than ever right now, we are urged to take a side, to be very, very clear in our opinions. To be black and white in where we stand. I personally have very few clear-cut opinions on any issue that is complex. There are a handful of issues for which I am very black and white, but for most things, even if I feel really strongly about them, I can see how one could feel differently. I can see what the argument could be for the other side. I love the essay because it allows for all of these things to come into the discussion. I love the essay because it is not prescriptive.

Going back to an earlier part of our conversation, I am of the culture in which I was raised. One of the things I was trying to get at in that piece was just generational differences. We as parents have this almost insane task of parenting a generation of humans who are growing up in a different time than we did. We carry with us everything that we learned, and I really hope with that essay, that parents could relate to it for numerous reasons. They wouldn’t have to have a gender nonconforming child to relate to the feeling of raising a child in an era that is different from yours.

You asked about the response I anticipated. My worst nightmare was that I was going to be met with horrific vitriol, that I was going to be accused of being a TERF, that I was going to be accused of being a transphobe for expressing any questioning. I’m sure those opinions are out there, I know they are. But I have to say, any communication that I have received directly has been overwhelmingly positive, and a lot of it from other parents. It achieved in that way exactly what I hoped, which is that I found those kindred spirits through my writing. It brings me such joy to know that, in some way, I have helped them feel less alone, but they, too, have helped me feel less alone. I think it’s incredible when writing can do that.

BY: The ending of the essay had me in tears. Jerald Walker, who has been a professor to us both at separate times, actually assigned this essay in a writing workshop I was in last fall. We discussed at length what the penultimate paragraph meant. It reads “Is loving the same thing as seeing? In this moment, I feel that it’s not.” Could you tell me about what that line means to you?

NL: To me, that line is the long, long lesson that I'm learning. I'm still learning about what it means to be a parent, but I think it also applies to what it means to love in general, which is that we can never fully know anyone, right? We can never fully inhabit their bodies, their minds. We can never fully see the world as they see it, or see them as they most hope to be seen. Because we can only see through our own eyes. We are limited. We are limited, as a lover, in terms of how much we can possess the beloved. We are limited as parents. Even as a mother, my children literally came out of my body, I'm limited in how fully I can possess them, right? They are their own people, and I think that loving the other is just a constant leap across a divide to try to accept people and embrace them for what they are, including what you cannot see and what you cannot understand.

There's the idea of the golden rule, right? Treat others as you want to be treated yourself, which I grew up with. And then one of my children informed me, at some point, that the golden rule had been revised, and that there was now something called the platinum rule. The platinum rule is to not treat others as you would want to be treated; it's treat others as they would like you to treat them. And I find that a problematic construction, personally. There’s that phrase “being seen,” or “I feel really seen.” We do all want to be seen, right? But there are limitations to how much we can be seen by somebody else. I think we're setting ourselves up for disappointment if we are aspiring always to be seen as we want to be seen. I think that it's a lack of compassion for other people if they're unable, for whatever reason, to see us as we want to be seen. That doesn't mean they shouldn't try, but I think we need to be a little bit more forgiving of one another in terms of how able we are to see others as they want to be seen, or how much others are able to see us as we want to be seen.

So to get back to that piece and the last line, I was struggling in that moment. It was a scene where I'm lying with my child in bed and reflecting on an experience we've just had. Part of me wants to keep chipping away at trying to get deeper into who they are. Really try to chip away at how they want to be seen. But in that moment, I felt like the most loving thing to do was to just let the unknown be. To just hold my child and be with them, and to understand that loving them in that moment might not mean knowing everything.

“That’s part of the beauty of an essay. An essay often does have this unfinished quality. It's like, this is the best I can do, or this is the clearest conclusion I can come to for now. There's always that open ended-ness.”

BY: One last thing that fascinated me about “As They Like It” is that the story didn’t feel like it was over by the end of the essay. You very fittingly end in a nebulous, uncertain place. Leigh is still growing and changing, as are you. It’s probably true of many personal essays that they are about stories that aren’t really over yet, but it jumped out at me here. What was it like trying to write an ending to an essay about something that is ongoing?

NL: I think your point here is very spot on: everything that we write, if we're writing memoir, has to end somewhere, but we can only end where we are. I was reading an interview recently with Lidia Yuknavitch. She was talking about The Chronology of Water and she says, You know, I am a different person now than I was when I wrote The Chronology of Water. And if I were reflecting on those experiences now, it would be a very different book. Not a better book or a worse book, but just a different book for where I am in my life.

That’s part of the beauty of an essay. An essay often does have this unfinished quality. It's like, this is the best I can do, or this is the clearest conclusion I can come to for now. There's always that open ended-ness. Just throwing this out there as a hypothesis, maybe for “As They Like It” in particular, that unfinishedness rises to the surface or is prominent because, when it comes to gender, we are trained to want an answer. Trained to really want to know, is this human male? Is this human female? Where does this human stand? I wonder if there's something about our desire when it comes to gender to want to have a clear-cut answer, something very binary. I wonder if that sort of highlights the unfinishedness of this essay.

BY: Something I absolutely loved about the collection was that each essay was in conversation with some other literature or research or media, which felt fitting, given your background as an English teacher. What prompted that choice?

NL: I wouldn't actually say that it was a choice. I think it was really organic, just because reading is such a part of my life. Given that every essay in this book was born from confusion, and given that, what I often turn to when I'm feeling confused or looking for answers is literature, weaving the literature in felt natural to me. If you're a reader, and by that I mean someone who deeply loves reading, I think you'll know what I mean when I say that authors can feel like friends, or kindred spirits, or life guides. I include so much literature in the book, because there's so much literature in my life. It's these things that feel really porous to me, reading, living.

It takes me a while to write an essay, a period of several months. While I'm writing an essay, I might also be reading something, and what I'm reading, whether it's a work of fiction, a novel, or whether it's something I'm intentionally reading because of the subject matter of the essay I'm working on, I start to see the world filtered through the book. That happens to us when we're reading, right? And then, conversely, I start to bring what I'm writing to what I'm reading. The boundary becomes really, really porous. I love engaging with the literature explicitly in what I'm writing, because it feels so integral.

I really, really wanted to give myself a challenge in writing this book of dramatizing the act of reading—not making research something that happened outside the frame of the book that I just kind of state from on high. There's a little bit of that. But for the most part, I wanted to bring the act of discovery into the book itself. When I'm reading, I don't feel like reading is separate from living. It's part of it, right? You are somewhere where you're reading a book. You might be lying in bed, you might be lying in a field on a summer day. It's an embodied experience. And I wanted to see if I could convey on the page the juiciness and sensuousness and life-altering power of reading.

BY: When it comes to writing personal essays, thinking about audience can be loaded, since some of the people who appear in the essays will probably read them. I was wondering if you thought about your children as audience while you were writing the essays in the collection. Do you ever think about how they might engage with the memoir when they’re older? Or do you try to set that aside as you write?

NL: Memoirists get asked this question a lot since they write about true people in their life. It makes sense because it's a fascinating question. One of the reasons it's a fascinating question is that we all want, desperately, as writers or memoirists, to have a clear playbook to fall on. How do you do it? Where are your ethical boundaries? It's fascinating because I think it doesn't have any correct answer. We are all kind of feeling this out as we go along. We're crafting our own philosophies, figuring out our own comfort zone, and in many ways, each essay in this collection instructed me how to go about this. There wasn't a one-size-fit-all approach to writing about loved ones or children. I'm always trying to write from my embodied perspective. What I can actually see, feel, hear, taste, touch with my own senses. Anything that is seen through their eyes, that's not my territory. That's not my story to tell.

Then the second thing that I'll say about writing about loved ones is, and I got this from my youngest kid’s second-grade teacher, is this acronym THiNK. It was a lesson that she did about speech and how speech is powerful, and how the things you say can hurt other people. It's very appropriate for second graders who might be hurting each other's feelings with words. THiNK stands for the questions that you should ask yourself before you say something. T stands for, is it true? Is what I am saying on the most fundamental level, true? Because as a memoirist and as a human, it has to be true. Then the second one, is it helpful? What I take that to mean as an essayist is not in any self-help way. Am I writing about my loved ones for a greater purpose, a helpful purpose, to readers? Or am I just throwing this in there? The next one, is it necessary? If I'm going to include this detail about my child, is it necessary to the story? Am I putting in anything more than I need to tell the story that I'm trying to tell?

And then the last one, and most important, is it kind? I don't put anything on the page that I don't think is kind. When I say kind, I don't mean nice, because there's a distinction. I don't mean to say kind in any saccharin, sugar-coated way. But is it looking at my subject with the ultimate well-meaning and compassion? That's just something that I apply to all my family and my children.

I've done a lot of thinking about writing about children. You asked your question very neutrally, but I think that there tends to be this sort of knee-jerk assumption that writing about one's children is an invasion. It's sort of reflexively thought of as a negative, as exploitative in some way, like, “Oh, you're using your children for your material.” I'm curious about that knee-jerk reaction because there's a long history of the old canonical painters, for instance, painting their children, right? Like Rembrandt or Vermeer using their children as subjects for portraiture. When we stand in front of a Vermeer painting of his child, no one is shouting “that's exploitative.” We understand that portraiture is a form of deep attention and regard.

The poet Mary Oliver wrote that attention is the beginning of devotion, and so when I wrote about my children, I really thought about it as an act of love and attention. I can't predict how they will think about these essays. I know how they think about them now. I've shared only the ones that pertain to them, I haven't shared my entire book with them. But just because they feel one way about it now, it doesn't mean that's the way they'll feel about it five years from now, ten years from now, fifteen years from now. In fact, I'm almost certain that they won't feel that way because we change, but what I hope is that they will feel, having read these essays, that their mother loved them so much that I felt they were deeply worthy of my sustained attention and contemplation.

BY: One last, much easier question as we wrap up! Which essayists right now inspire you?

NL: Oh, gosh, well, I have to say Jerald Walker. It's always got to come back to Jerald. Jerald Walker, I've learned so much through reading his essays about concision, about both-and-ness. We write about very different things, but to reveal how he is, he explores how he is of the culture and critiques the culture.

And I'll just name some of my favorites: Jo Ann Beard, Eula Biss, Claire Dederer, Jia Tolentino, Kathryn Schulz. I tend to love nonfiction writing that is both intellectual and ruminative and esoteric, but also really, really embodied and physical. I think all of those authors do that really well.

See also:

“Shake Zone,” The Cincinnati Review, 2023.

“Tikkun Olam Ted,” River Teeth, 2021

“Tight Jeans,” The Hudson Review, 1998; listed as Notable in The Best American Essays 1999.

Bayani Young is an editorial assistant with The Best American Essays. They study creative nonfiction and teaching at Emerson College to prepare them for a career as a writing educator.