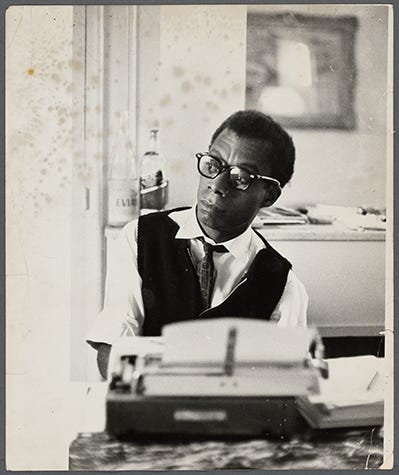

In Memoriam: James Baldwin

Died December 1, 1987, Saint Paul de Vence, France

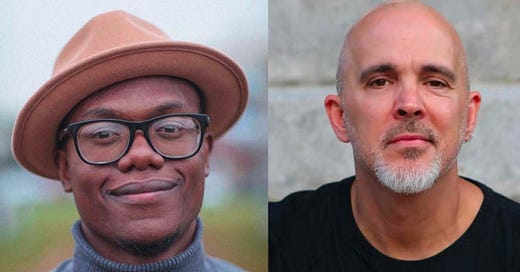

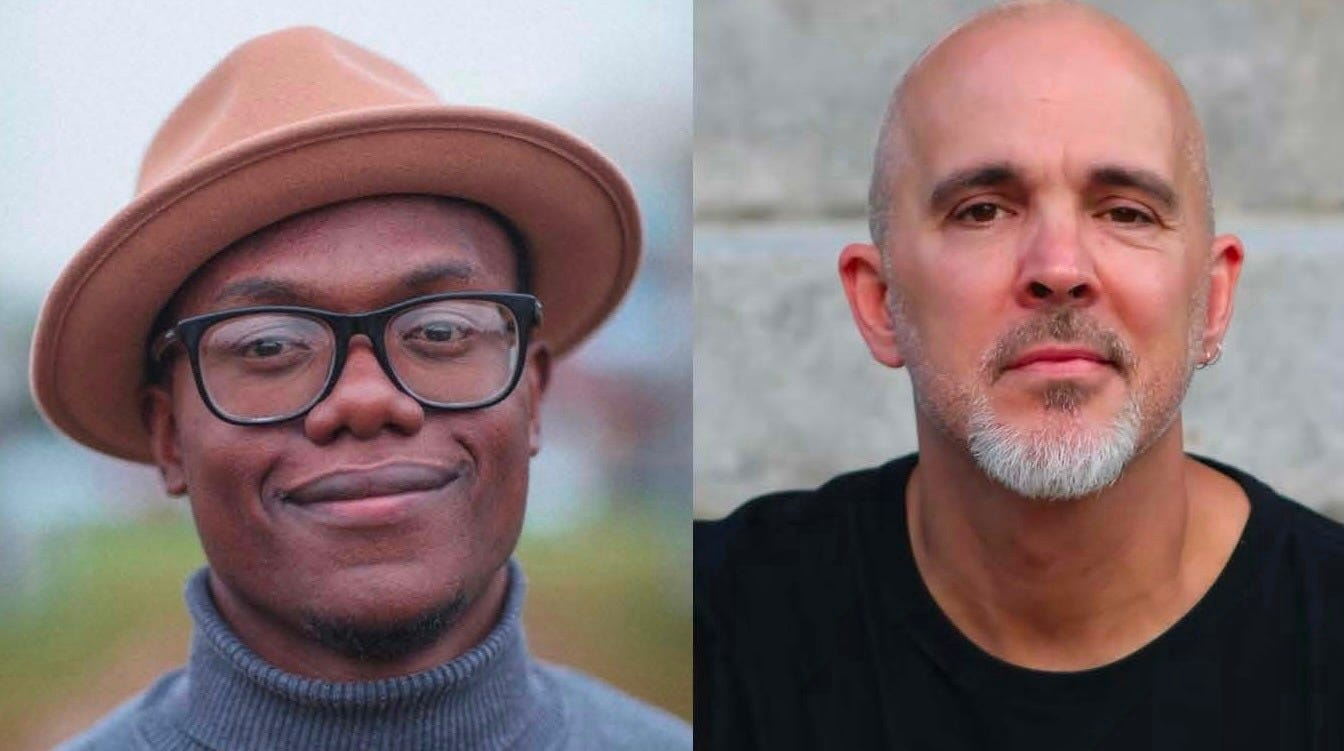

A Conversation with Rémy Ngamije & Ed Pavlić on the 37th Anniversary of James Baldwin's Death

To commemorate the thirty-seventh anniversary of James Baldwin’s death, Best American Essays 2024 contributors Ed Pavlić and Rémy Ngamije talk about their relationship to Baldwin’s work. For more about Baldwin, see the post celebrating the centennial of his birthday.

On Encountering James Baldwin for the First Time

Ed Pavlić: I was a teenager living in Wisconsin, with my mother in 1982, the two of us, in an all-white town where she had gotten a job. And, for whatever reasons, I think basically because of the way I came up and the way I had learned to move through the world and certainly the way I expected the world to move through me, my presence in space—in school, socially—became a great controversy in this little town, and it turned out it was, in the minds of people around me, a racial controversy. I was sixteen and I really didn't have ideas of why this was happening, but it was still very confusing. I couldn't find any adults around me who seemed to know anything about what was happening to me or really what was happening to other people.

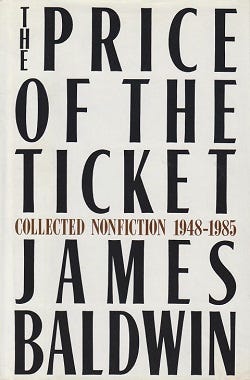

I had a girlfriend whose mother—and I have no idea why—had acquired a copy of The Price of the Ticket, James Baldwin's collected nonfiction, when it was first released. I remember my girlfriend handing me this book and saying, my mother wants to give this to you, and we wonder if it could help you. I don't know if I had even ever heard James Baldwin's name before that when I was a kid. In terms of literary history, we know now that Baldwin's ascendency as a celebrity and a kind of household name in American culture was at a low point by the mid 1980s. If I had been born twenty years earlier, there's no question that I would have known his name and have seen him on TV. But by the time I was a teenager in the early eighties, he just wasn't as conspicuous a part of the culture as he had been before. I wasn't from a family that considered itself in conscious and literary and artistic terms in any meaningful way.

[Baldwin’s work] just wasn't something I was familiar with. Neither was I much of a reader at the time, as a kid. So I looked at this book, and the book is huge. You know, it's, like, 700 pages long. I was holding this thing thinking, What am I going do with this big-ass book? I looked at the table of contents. I remember going down the list of titles. And right about in the middle somewhere, I came across a title, “Color.” Just one word, color. And I thought, This might be helpful. Plus, I saw from the table of contents, [that the essay was] five pages long. This was something I thought might be to my advantage as well. The essay begins: “White people are not really white, but colored people can be extremely colored.” And I thought, Oh, okay, that's a strange sentence. But even then, right away I could see that things in this sentence were shifty and fluid in ways that the world around me thought were very solid and stable. So I kept reading and I came across in that essay an appreciation for cultural space. And the idea that color and culture were very real and complex things, and that race itself was a kind of murderous lie slammed down the tops of people's heads. All of that seemed very, very clear to me when I started to see Baldwin laying it out in those paragraphs. And even more than that was this totally new sensation to me, to be seeing in lines of print on paper—exposed in a kind of clarity—things about my life and my world that were very, very turbulent and mysterious to me. I had never had that experience with a book before, because my relationship to schools by then was a disastrous thing. And so I went through that essay, “Color,” and Baldwin was basically saying that when Black people predominate in a cultural space there's a certain sense of presence that results. There's a certain sense of connection between people in Black cultural spaces. He's thinking of uptown nightclubs in New York City in the early sixties.

I had never been to New York City in the early sixties. But there was a sense of togetherness and a sense of proximity between people that I knew very, very well. I knew it as well as anything I knew in the world. And from the time I was a kid, I had aimed myself at exactly those places. Then he says, no matter how prestigious the location is, when white people predominate in a cultural space, something empties out of the air. Something vacates from those spaces. No matter how much people have paid, and no matter how great it's supposed to be there, something's missing, like molecules from a solution. I'm paraphrasing, of course, but that's the gist of that piece. And though I had never been to New York City [and] had certainly never been to nightclubs, I could really understand and comprehend what he was saying. I had been through that. I had felt that. I had felt it in schools, in playgrounds. I felt it in my own house. And in the houses of friends, Black, and their families. So that was my introduction to Jimmy Baldwin. I got to the end of that essay. The next one was “A Talk to Teachers.” And I thought, Oh, well, hey. You know, if color is one problem, teachers are the next.

Rémy Ngamije: That was a wonderful way to say how you met Jimmy B because I think everyone has that weird introduction to him where they're like, wait, is this on a page? And then it feels so fresh and so recent. And then you [realize he was writing] in the sixties. How is this relevant to this day? I think for me, when I read first read Baldwin in university, I was maybe around twenty, twenty-one. I was really, really struggling with the idea of who I was because it felt like I was being boxed in in various things.

But Jimmy spent his whole life trying to not be boxed in any one thing. It's like whatever box you're putting me in is because society has told you I'm this person, that I'm a black person, that I'm a black man, that I'm a gay black man. And, you know, it all is summed up in the title, which I think is one of the coolest titles ever: “I Am Not Your Negro.” And he says, I am not your neighbor. If I'm your neighbor, it means that you own me.

These contradictions that he has in the language of the everyday really brought the idea—as you said, Ed—of fluidity, that the contentions we have about ourselves and the world around us are not as finite as we think they are, and that they change depending on perspective, time, age, maturity. And that hit me the same way with this idea that […] the opposite of being white is being Black. Baldwin writes in a way where he asserts things in the positive or the negative. And by the way that he writes, you can see the opposite, and that's such a clever way of writing.

On Baldwin’s Appeal to Love, His Anger, Timeless Timeliness, Intimacy, and Permanence

Rémy Ngamije: How he affects you initially is as a reader; he [navigates] spaces that no one else is talking about at the moment. And there’s that amazing feeling that you've just entered into someone's mind, someone who gets you. It's very hard to distinguish between Jimmy's influence on me as a writer and as a reader. The first thing I encountered with James Baldwin is how relentlessly and tirelessly angry he can be. There's that fury that never ends. But within that fury, there's also softness and gentleness and an appeal to love and to beauty.

That for me was a shock as a reader because I've struggled with the societal things suffered by a young immigrant on the continent, which didn't find an outlet. And then I read James Baldwin, and I thought, Oh, it's perfectly safe to be angry, but to also have these moments and flashes of beauty that in a lot of ways are actually the reason why you're writing in this tone, in this way. And so with my writing, when I started, I had a regular column in the newspaper, it was a case of [switching on] this anger—I was angry about a lot of things back then. But also at the same time to look back and say, but why are you angry? Well, you're angry because this situation is ugly, but it could be better.

And let's try and flip that, show the wound for what it is, but then also try and show what it could be if we're to heal things properly and, if we're to give people fairness, equality, justice, if we're to love each other as common brothers and sisters rather than loving each other for the things that we can do for each other through economics or whatnot. That [realization] changed my writing because it was an amalgamation of not just righteous fury, but [an understanding that] there's so many things wrong in my environment that I didn't have the language to address. James Baldwin's work gave me that. Not only was he fierce—very intellectually fierce—he was also very gentle in his writing, and I found that captivating that you could be these things [at the same time]. That you could write about love in very gentle ways, and that you could actually speak about love publicly as a Black person. And he was doing it back then.

We were very scared about having these conversations in the modern times. I'm talking about 2016 to 2021, but we were having these problems with talking about love as ordinary human beings. And that, for me, really changed my writing [and allowed me to] be courageous enough to have these conversations about love, about common humanity, about brotherhood, about sisterhood, about just sharing a space together.

And one thing besides the intellectual capacity that he had, one thing I don't think James Baldwin gets his flowers for is how beautiful his sentences are. He writes very, very beautifully. He makes a lot of political points, and that's the purpose of his writing. But the vehicle that he chooses to get you there is language, and his sentences are absolutely beautiful.

There's no writer, there's no book, there's nothing that won't be affected by time. So being timeless is pointless. But I believe in timely writing. And that's what I've always found in James Baldwin's work, that it is timely. It always seems to come and be relevant at the moment when it is most needed to be relevant.

The titles that he chooses, the way he starts his essays, the way he frames the premise or the conclusions, it's resonating and it haunts you. And that is the aspect of beautiful writing, an aspect of writing that I aspire to. How do I write in a way that transcends or that is timeless, but in a way that is timely? So that when you read this five or ten years on, it makes sense?

Because there's no writer, there's no book, there's nothing that won't be affected by time. So being timeless is pointless. But I believe in timely writing. And that's what I've always found in James Baldwin's work, that it is timely. It always seems to come and be relevant at the moment when it is most needed to be relevant. And that for me is something that I aspire to do within my own work.

Ed Pavlić: This question of relevance and timeliness has been something I've been thinking about lately. Recently, in another context, the question of Baldwin's relevance came up. I remember saying that with an artist of Baldwin’s caliber, it’s [more a] question of permanence. You know, his work is permanent. Its importance is permanent. The question of relevance is really on us. Are we relevant, both to the permanence of what he created, but really even more than that, are we relevant to each other… and how? Because Baldwin's primary and most crucial message is that people, as a species, are part of each other whether we like or not. We are we are already part of each other, and there'll be no peace unless those relationships can be improved. Often our impulse in problematic relationships is to recoil and depart. Baldwin did his share of that. But somewhere around the middle of his career, he realized, it doesn't work. These troubles need to be engaged.

Baldwin's primary and most crucial message is that people, as a species, are part of each other whether we like or not. We are we are already part of each other, and there'll be no peace unless those relationships can be improved. Often our impulse in problematic relationships is to recoil and depart. Baldwin did his share of that. But somewhere around the middle of his career, he realized, it doesn't work. These troubles need to be engaged.

As far as Baldwin's place or importance or role in my life as a writer, it's hard to frame it because his, his importance to me is beneath the questions of being a writer. His importance to me is primarily a matter of living: How do you stay alive? How do you keep yourself coherent enough to function? And his work has been a part of my survival in that kind of most immediate sense. Of course, part of that survival for me has been writing. I've had to work my way into that and I've continued to try to work my way through that. And I think, you know, there's a thousand ways to talk about that, but I guess maybe, the most important thing to focus on is the sensation in Baldwin's work of intimacy and closeness and his insistence that we not romanticize intimacy and closeness, that in intimacy and closeness, there's in fact great danger. The people we love the most are most dangerous to us in certain ways. In other ways, strangers, of course, are lethal.

I think of the great importance of the singer and writer Billie Holiday to James Baldwin, the artist. And I think Billie Holiday's art is about exploring and clarifying and then dramatizing and communicating people's great power and danger to each other. The question of lovers. And, inside of all that is just the sheer need and power of human touch. And I think Baldwin's writing, unlike any other, carries with it the sensation of human touch. And that's something that I think inside of every sentence, every syllable that I really care about in terms of my own writing, I'm striving for, is that that sense of closeness, that sense where words and the sensation of human togetherness and even the friction of human contact, skin on skin, eye to eye, soul to soul is at stake. Who knows what psychiatrist or psychologist could tell me where this need arose in me as a child, but I just don't usually feel as if the world is close enough to me in daily life. At some point, my attempts and experience to bring the world close and to throw myself close to it, proved themselves to me in such a way that made me think to myself, I should try this out on paper instead of in the street.

Ever since, I've been aware of that, in my first poems and all the way through to my most recent writing. Really no matter what kind of writing, I just think that I'm leaning my nose close to the page, and the idea is that there's a reader kind of coming up to the surface from the other side. And in that writing, we come together. We come together maybe more closely than in any other way, which seems to me to make it all worthwhile. Otherwise, it's hard for me to consider writing and reading in ways that differentiate it from the act of leaving. You know? I needed to work on this for quite a while, I think, as a person, to come to terms with reading and writing as a way of coming toward the world, of not hiding from the world. And Baldwin seemed to have worked that contradiction out, you know, very early as a writer, and also as a person.

On Teaching Baldwin: An Eternal Act of Apprenticeship

Rémy Ngamije: [Teaching is] something I definitely wish I could do, but the opportunity has not materialized. I do know the reaction people have when I recommend something from James Baldwin. And it's often a question about why. Later, I get the shortest response, like “I get it.” Writing is an eternal act of apprenticeship.

Ed Pavlić: Students' responses to Baldwin's essays and his work in general are variable. By and large, the student responses that I can recollect are more sophisticated and generally far better than the record of his book reviewers, who were supposed to be grown-up, professional literary people when they did these reviews. Something interesting is going on between Baldwin and his mature readers that I don't always find going on between Baldwin and his apprentice readers. And it seems as if Baldwin is a writer that in some ways people latch onto very powerfully, very quickly, and then something goes on that that comes in the way of that proximity or that regard or whatever.

The other thing I’ve done in a lot in classes that has been a really powerful thing is to play recordings of Baldwin speaking. Sometimes of him reading, sometimes in interviews, sometimes giving talks, sometimes video recordings where you watch and listen, and sometimes only audio recordings, you know, where you can't see.

Baldwin's voice—in person, in real time—is related to his voice on the page, of course, but, it is also particular, and bears a really powerful resonance. I remember when I was an undergrad, maybe five or six years after I had been acquainted with his writing for the first time. I had kept reading The Price of the Ticket. And here and there, I had a class where his work would come up, a novel here or there, certainly, Go Tell It on the Mountain. At some point, I think it was a classmate of mine who said, “You know, you're always talking about James Baldwin. You could probably find copies of recordings of him in the media center.” I went up to the library and asked the librarian. She came back with two cassette tapes, of Baldwin, and I played them on my little Walkman at the time. I put my earphones on, and I remember thinking, Oh god… What if I hate his voice? What if it's a terrible disappointment? This happens sometimes with a writer you really love. You hear him speaking and think, Oh, damn. That's how they sound? I remember his voice coming on—it was an interview—and listening to his voice for the first time, thinking, This is that same guy. But living in a different way in my ear than it does in my eyes as a reader. This is a wonderful experience.

Listen to “A Conversation with James Baldwin,” WGBH Educational Foundation, 1963.

One other thing about teaching Baldwin's essays, is that after his first novel and maybe his second novel too, Baldwin started to place an essayist kind of content into fiction. And this gained him the opprobrium and the disapproving of many, many literary critics still today.

But my favorite writing of Baldwin's is this essayistic content embedded in a fictional form. And so, my favorite experiences with students and Baldwin's essays are often from teaching his novels, especially his final novel, Just Above My Head, which is his most essayistic novel and also his greatest achievement in my mind with no close seconds. I think it's his greatest book, and, I'm a kind of apostle of a certain kind, promoting people's greater acquaintance with that novel because it has not been a well-respected novel of his. It's one of his least read books. And it's absolutely without any peer that I know of in modern literature. So there's the plug for Just Above My Head as a kind of lyrical trans-generic, essayistic, incredible achievement that he published late in 1979.

Editor’s Note: Rémy Ngamije’s “Love Is a Washing Line” and Ed Pavlić’s “Anita Baker Introduced Us and Patrice Rushen Did the Rest” appeared in The Best American Essays 2024, reprinted from, respectively, Prairie Schooner and Oxford American. Each essay represents a different kind of love story: Ngamije’s is about a married couple, and Pavlić’s is about a friendship between two young men.