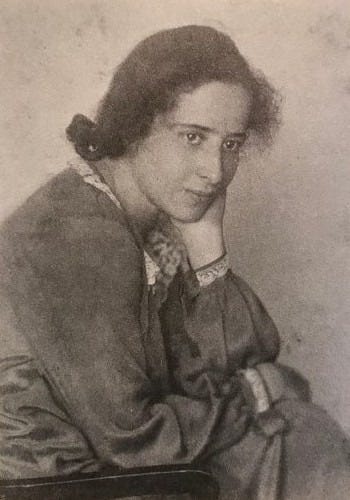

To commemorate the forty-ninth anniversary of Hannah Arendt’s death, the Best American Essays newsletter reprints Baron Wormser’s essay, “Hannah Arendt in New York,” which appeared first in Solstice, Winter 2017, and was reprinted in The Best American Essays 2018, edited by Robert Atwan and Hilton Als.

For more about Hannah Arendt (born October 14, 1906, Linden, Germany, see the post celebrating the 118th anniversary of her birth.

Hannah Arendt in New York

She has witnessed rant that silenced every reproof. She has waited for some larger affirmation to arise, the vision of decency, but none came. She has heard the triumph of jack-booted certainty strutting to the mob’s approving roar. The precious freedom that a republic cherishes, the freedom to seek truth in the face of falsehood, can dissolve like a book left out in the rain. Heinrich, her edgy, shrewd, passionate husband who fought on the streets of Berlin is that precious, more precious, but without this freedom he would not be alive nor would she: two more corpses in the ideological charnel house of Europe. She does not doubt the burden: people must be ready to die for freedom, but the reasons must be honest ones. All the standard human debilities—greed, prejudice, sloth, ignorance, hypocrisy—are woven into freedom’s cloth. Working as she does in the service of reason, she spends her life disentangling those threads, which is, in the twentieth century, a colossal joke. Some days she broods; some days she forgets. She is only human herself. At odd moments, Heinrich gently reminds her of that datum. He points out a tic in her German or a run in her stocking. They laugh together. There is something remarkable about their laughter. It is resonant with the distress and joy of time, moments that include kisses and years shattered by the hyphenated demiurge the two of them call “World-History.”

History is the unexpected that is then parsed out as the expected. “Ah, yes, the world wars, Hitler, Stalin, revolutions, the atomic bomb, ah, yes, we saw it all coming. Here are some explanations.” The human capacity for arguing backwards is as bottomless and frightening as the human capacity for accepting whatever comes marching down the disastrous pike. She and Heinrich are not mass people. The entertainments that light up Times Square could disappear tomorrow and for them there would be no loss. It isn’t that they don’t have fun—a word Americans are fond of. They are lots of fun—drinking, talking, and giving parties where people occasionally make tipsy fools of themselves. Their New Year’s Eve parties are famous. But someone like Plato is likely to show up in their talk, a candle from the dim vault of profound endeavor. Would it be fair to say that Hannah is more at home with the philosophers than with the people down the hall? Sometimes she worries about that. She is an instinctively warm person. So many philosophers were cold men intent only upon the vigorous elaborations of their unhappy brains. They constructed intricate systems to catch flies.

She is safe in America—and thankful for that safety—but she is always looking over her shoulder. She turns around on a street off Broadway and sees only another New Yorker in his or her coffin of an overcoat. The sight reassures her. She goes forward on her errand, but for her larger errands there are no reassurances—nor should there be. Everything is fraught.

The person in the overcoat walks on unperturbed by the fraughtness. What would the German noun for that be? English is a terse, physical language incapable of those long words that gobble up short words. The German language was made for philosophizing. German honored the invention of entities. English was made for ordering fish.

How could a nation go so wrong? The first answer might be that it never was right. It wouldn’t be a bad answer.

She turns around again to watch the person. She has dwelled inside of life’s fraughtness—love affairs, emigration, fanciful yet demanding conversations into the early hours of the morning—but she is outside, too. How could she ever have imagined she would be living here in New York City? Her childhood in Königsberg seems immeasurably far away. There were still landaus and teams of great, shaggy horses to pull them. There were rose gardens. There was the silence of a world before the advent of so many machines. German history, though, can clear any nostalgic vapors.

Juden raus!

How could a nation go so wrong? The first answer might be that it never was right. It wouldn’t be a bad answer. Heinrich has proposed it to her more than once. Germany was never benign. As a nation, it had from the beginning too many dire myths rumbling in its stomach. The Jews always lived on a window ledge there. Good citizens, they partook eagerly of whatever crumbs were offered them; they made themselves comfortable on that ledge. They dressed properly, spoke properly, and educated their children properly. They loved German culture with an almost indecent passion. Hannah could quote Goethe and Heine with the best of them. If Jewish life was historically built on wariness then the belief in assimilation was all the more understandable. The Jews wanted to be part of the world that was Germany. Hannah was part of that world.

In her apartment are books and tobacco. Cigarettes give each day a harsh yet agreeable edge. A flourish of sorts, they intensify both the longueurs and flashes that go with thinking and conversing. One draws in and then expels. One reads and writes. Periodically she airs out the apartment but the city is dirty with the exhaust of smoke stacks and autos. That is as it should be. People are here to make money. The United States, as she once informed her mentor Karl Jaspers, is “a society of job holders.” That is a fragile cohesion; everyone busy at whatever task they deem worthy of their precious hours. But maybe it is no more fragile than any cohesion. It emanates from the people. No king or church decreed this endless American labor. It makes for a bustling solace. Everyone has something to do. There are not so many grievances here. Yet she sees Negroes every day. There are plenty of grievances.

She has never been one for teleology. Ends tend to be lies that placate the means. Ends dwarf any mere life. What remains appalling to her about Germany was the eagerness of people to give themselves up to the ends and their indifference to the means. What happened there had nothing to do with the patient work of thinking but with faith gone wrong. Faith should be humble. Faith that is vengeful is a nightmare. So the ghastly assertion: Germany is a great country that must avenge itself, and part of Germany’s greatness is its willingness to stand up against the forces that compromise its greatness. Murdering children—what a sign of greatness! Sometimes Hannah finds herself shaking her head on the street then she realizes other people shake their heads, too. They, too, have their inner conversations. They, too, carry within them the splinters of the past.

There is in this world no shortage of matters to despise. She can be a despiser. People that turn away from making judgments are at best too comfortable, at worst cowards. She has seen people be tested by history and fail. Many were friends of hers, people who, it seemed, shared her values and beliefs. One was once her lover. How hard for her to get that straight, to understand how a person of such depth could be susceptible to nothing more complex than the afflatus of hatred. Heidegger thought he was going to stand on a world stage. Trumpets would sound all around him. Spirits would levitate. The impulses that over two thousand years ago fashioned the tense embrace between the mystical and the rational would reappear with him as their emissary: a dream to mock all dreams. Yet something remarkable stirred inside of him. Though she was not much more than a girl when she went to bed with him, she knew that. Taking him into her body was like taking something imperishable into herself, something beyond flesh. If there was plenty there to shake her head about, there was nothing to regret. She had welcomed him. She had been flattered. And she had yearned for him. He trafficked in the impossible. He wasn’t a modern man. When history knocked on his door, he thought it was his own legend summoning him. Alas, it wasn’t. But alas was far too weak a word.

Juden raus!

Aspiration makes for a dangerous compound. That seems one of the beauties of living in the United States. There are no essences to aspire to. Beyond what a ball player can do, no one cares about greatness. The shop windows hold what is within reach. Money, in its fairy tale potency, beckons and inveigles. She, too, enjoys lingering to look at a pair of shoes or a dress. The call to something higher has little appeal when considering a hem-line or fabric. The vanity, whether mild or deep, that underlies every look in the mirror abets the commercial republic. That, too, is as it should be. People cannot escape their bodies nor should they want to. What destroyed Germany was the frightening mix of medieval and modern, obedience and degradation, kings and factories, everything wanting to be over and above and beyond, a Götterdämmerung of unsanctified emotion. Here, beyond the endless slogans, there are no sirens. The storefront medley of prices, bargains, and sales that accompanies her route along upper Broadway to the butcher, the grocery, and the five-and-dime is tawdry but blessedly mundane. Though no advertising agency is going to seek her out to pose for a photograph, she can appreciate the goods America dispenses: she is at home with her refrigerator as much as the next hausfrau.

How wrong that opponent of the mundane Karl Marx was! To think of him in the context of her daily life is almost humorous. A vengeful man, he could not accept the tangible rewards of capitalism nor could he believe that work might be more than a victim’s begrudged labor. He lacked the combination of yearning, desperation, and common imagination that drove so many to America’s shores. Instead, he sat in England and drove his pen to prove his loathing of the bourgeoisie. What he possessed, like many a Victorian, was a taste for fairy tales, only his fantasies ran elsewhere: the state would wither; labor would be replaced by higher activities; the working class would triumph.

The depredations of her adopted country are what they are. They have been practiced on the Negroes as something like a folkway, at once vicious and matter-of-fact. But there are laws and they can be brought to bear. There is a constitution. Marx, despite the shelter Britain afforded him, did not have a respect-for-the-rule-of-law bone in his prophetic body. He saw the careful precedents of justice as one more fraud. Those precedents can and do fail, as they have failed the Negroes, but democracy allows people to persevere. Such perseverance annoyed Marx. People with their quirks and peccadilloes annoyed him. A believer in the genius of theory and systems, he was one more progenitor of the false sciences that captivated the nineteenth century and set fire to much of the twentieth. He provided the justification for absolving any semblance of conscience: the masses—to say nothing of those who led the masses—have the right to bury the individual. Bury was not an exaggeration.

How many European intellectuals still worshiped at his sooty altar? Her husband once did. How many replaced God with history and a handful of exhortations? How many of them secretly believed that Soviet man and woman were better creatures? And how many despised America because it was irredeemably mediocre—the home of chewing gum and hair tonic?

Understanding the new nation has taken time. She would have been glad to live in France or, of course, Germany, but World-History ordained otherwise. America is such an unsettling mix of social friendliness and political covertness, of the prosaic and the idealistic, of oppression and freedom, of modern times grafted onto the world of 1776. For someone who has spent her life beginning many a sentence with “Why,” America is bound to shock. That is the last question anyone cares for here. What matters is what you do, not what you think. It is hard for her to imagine a nation not as the complex sum of centuries but instead as an enterprise where everyone strives to achieve happiness. Happiness! Despite the brisk handshakes Americans exchange and the psychological explanations they lap up, happiness is no business. To found a nation based on the pursuit of happiness was to invite the personal into the political in ways no one could imagine. Hannah, who relishes etymologies, is quick to point out that hap means chance, luck, fortuity.

From chance to tragedy is a half-step, as when her friend Walter Benjamin committed suicide because on the particular day in 1940 he tried to enter Spain, he was turned back. It is the trail of steps that led her sister to commit suicide. Clara had sought love she never found and wept often about her unhappy fate. Was it her fault the men she pined for did not respond? To talk of happiness can be very cheap talk.

Perhaps the lack of consolation is what the consolation of philosophy can best teach. Abstraction is a dubious consolation, more gauzy absence than actual presence. Jaspers likes the word “concrete” to describe what philosophy must be. The real rigor of philosophy is to keep the world in front of you and not elevate or subjugate it. The real consolation is the integrity that may reside in thinking and the choice of not surrendering to the hypothetical. In that sense she feels at home in America. The clamor about what irrefutably exists is genuine. If it is short-sighted, a species of perpetual-motion machine, it is preferable to some murderous, sovereign goal. “Everyone here is busy. Everyone here muddles along.” That would be another conundrum to chew on as she walks the short blocks of Broadway.

Some days there is literally music in the air, not the classical music that her sister Clara practiced on the piano and that Hannah was taught to adore, but popular American music. Stores on Broadway sell radios, record players, and records. She has found herself standing outside a store on a warm day and taking in the sound. “Noise,” poor Clara, who played the piano beautifully, would have called it: no rapture, no grandeur, no impassioned sensitivity. To Hannah, who to her mother’s chagrin had no special musical aptitude, the songs, however thin they first appear, are wonderful. They lack the cabaret edge of Weimar but are blessedly free of indulgent German sentimentality.

Someone named Dinah Washington is singing “September in the Rain.” Hannah stands there—it is July—and listens. The woman’s voice is full and sweet, precise and gracious and, in its crisp yet feeling way, exquisite. What more, Hannah thinks, could we ask of life? A Negro woman stops beside her and also listens. Here is a spontaneous plurality.

Maybe until you have lived fearing a knock on the door that will mean your death, until you have experienced how the arbitrary and wanton can be a law unto itself, you cannot understand the importance of civility.

Too often, politics, with its necessary focus on the plural that is the people, is wrong-headed. “Society,” Tom Paine wrote and she has quoted, “is produced by our wants, and government by our wickedness.” Our wants are like the songs: love me and understand me. But our living with one another, our plurality, is something else. Conceit and distrust bleed into our mutuality. Degradations become accepted manners; cultivated loathing overturns whatever modest civility a society may have achieved.

Maybe until you have lived fearing a knock on the door that will mean your death, until you have experienced how the arbitrary and wanton can be a law unto itself, you cannot understand the importance of civility. The United States of America is the result of a revolution—an uncivil act—but one the world has yet to understand, an obscured and partial revolution tied to the rights of the individual. How are such individuals from all over the globe supposed to make a political society devoted to something other than glorifying selfishness? Does one right get in the way of another right? Do individuals start to see themselves as compendia of rights? Do they invent new rights? How are the rights shared if they are rooted in the individual’s actions and sense of life? Must the exigent force of economics make a travesty of rights? And who were the people who created this nation and its constitution? Who, compared to Hegel, Marx, and Heidegger, was the slave-holding gentleman named Thomas Jefferson? In trying to answer those questions she is trying to assess the nature of that revolution. The revolution in America rarely impressed her leftist, European friends. A tolerant, wary, eighteenth-century view of humankind seemed beside the point in modern times. Yet here was this nation.

If human nature is unknowable, like the German saying about jumping over your shadow, then every political system is a less-than educated guess. The challenge is to balance your guesses based on what you know about human beings—their wants and their wickedness. One of the errors of modern times was to disbelieve in wickedness. On the shelf of idiot bromides, progress stood out as one of the most stupid. Hegel—to choose one of her German forbears—was barking at eternity: history had no immanent direction. As a man entranced by teleology, he lacked a feel for his own conceit.

She has seen the wickedness at first hand. Juden raus! Those two words are the gist of many lifetimes; grief and calamity linking hands over centuries. Though she never goes to a synagogue, she is adamant about being a Jew. Like many a modern person, she knows that she has replaced God with the world. She can’t help herself. The thread that connected her to the divine was snipped. The political news she retails to Jaspers in her letters about Joe McCarthy or Adlai Stevenson or the dubious character of Lyndon Baines Johnson is not the stuff of piety. Too often, it is the stuff of low-minded democracy, of rumor, calumny, and supposition.

Does this mere spinning world give a person sufficient light in which to view wickedness? There are examples and reasons—some better, some worse—but the light is something different. She and Heinrich talk about that light. She, after all, wrote her doctoral thesis about Augustine. To dissolve human wrongdoing in the great encompassing light of God is terribly easy. God diminishes mankind. Mankind exalts God. God exalts mankind. Mankind diminishes God. Such a topsy-turvy relationship is awful and comfortable at the same time like a child who will not stop shaking a rattle.

She has her particular fears, not only the mortal ones such as that Heinrich will die before she does, but ones that have no dimensions. Those are the modern fears bred in the bones of banality, a word Jaspers used in a letter to her after the war. The word is an answer of sorts to the obedient wickedness of functionaries but not an answer, more like a gambit. The problem of evil, as she has termed it, is, however, no chess game.

How can a condition be a problem? How can myriad acts contain one seed? How can reason apprehend the depredations of spirit or worse, the blankness of spirit, the vicious emptiness of the bureaucrat Nazi Eichmann doing his job and complaining about his rivalries with other functionaries? And doesn’t “problem” insinuate an answer? Doesn’t “problem” contain a mocking overtone: Hannah hefting her small, resolute shovel before a mountain of confusion? Banal or not, evil is bred in human bones. Other animals cannot do it. So all the categorical human issues—will, volition, choice, responsibility, morality—congregate outside a philosopher’s door and beg to be heard. Philosophy, as Heinrich’s beloved Socrates demonstrated, is an unlucky and largely unwanted practice. To do it is to suffer it.

Hannah suffers gladly. She has that outsider gene. She is the one who will always ask the uncomfortable question, the one who falls, as she says, between the stools. There is some pride in her about this. There is some contempt for those who refuse to follow the trail of questions through the tenebrous woods. There is ardor, too, though, and something like love. Because she loves to be in the world, she feels she owes the world her complicated honesty. Whether the world wants such honesty is, as she would be the first to testify, another story.

Perhaps what ailed Germany has ailed her, which is one reason she went to Eichmann’s trial. Amid the famous German efficiencies—getting trains to concentration camps on time—there is the metaphysical impulse, the belief that thinking can be more than window dressing for prejudice. Questions and problems beg for solutions: Hitler, though not a metaphysician, had a final one. Of course, to impugn philosophy in that regard would be unfair. Philosophy is provisional, part of a western tradition of thought-work that has striven to be impartial, though not objective. Judgments are crucial to living on earth. Without the judgments bred by conscience human beings are lost. To be objective in matters of heart-feeling is to surrender one’s birthright. It grieves her that so many have been so eager to do so. Inhumanity is not an idle word. It means something very exact.

Juden raus!

Adolf Eichmann seemed in that glass booth a small, middling person, in his earnest way ridiculous. His certified Jew-hatred—how else had he managed to occupy such an important position?—took a back seat. Time and again over the months of his trial, he spoke not to his zealousness but to his honor and his deportment. He scraped before his betters and looked down on ruffians. He admired Hitler for making something of himself. While extermination was being organized on a scale hitherto unimaginable, he worried and chafed about his career. He confessed himself happy at some times during the war and frustrated at others. He took satisfaction in doing a good job, in being an expert of sorts about Zionism. He relished the tepid oblivion of cliché. This Nazi, he declared, was “brilliant,” that one was “untrustworthy.” As a bureaucrat, officialese gave him great pleasure.

The deaths—to descend into the world of words—were ghastly but the fact of this man insisting on his career was also ghastly. Hannah Arendt’s tone in her reporting on the Eichmann trial was tinged with exasperation and sometimes with sarcasm. Who could fathom the disproportion between men sitting at their desks with their requisitions and the naked men, women, and children waiting to take their death showers? Who could take the measure of modern times that promoted the genius of machines and machine-like behavior? Who could hold those euphemisms—“resettlement,” “evacuation”—in his or her mouth and not choke? Perhaps what the world needed was not philosophy but a new Bible.

Despite her doubts—or because of them— she persevered as a free person is supposed to persevere. She touched on the obedience that the Jews were locked into, their filling out the endless paperwork the Nazis required of them, their standing in the lines that took them to their deaths. Many Jews howled at Hannah’s written touch. They felt she was unfair, unfeeling, and little better than a traitor. Despite her intelligence, she was naïve. There could be no qualifiers to the hideous, larger truth. But for Hannah, who was trained to consider the whole topography of truth and was steeped in the modern literature of desperation, there were such qualifiers, just as Eichmann had a grotesque, comic side as he sat there and clarified points of order about how he did his job. He was eager to speak and explain. He wanted to set the record straight. He may have been acting, putting on a performance while inwardly baying at the most horrendous of moons. To assert his enthusiasm as a Nazi would have been very bad form. Yet there he was, quite composed, ready to argue some peccadillo about the murderous protocols. He would, as they say in New York, “do anything to save his own skin.” His testimony may have been nothing but lies but it still was testimony. He had been there. No one argued that point.

She thinks about this Eichmann as a representative of the human race. To assume that any given person has a conscience is a big assumption. To assume that the conscience has some depth and is something more than petty self-righteousness is a bigger assumption. The endeavor of philosophy, her life’s endeavor, is to examine assumptions. Her husband, who is a living representative of the Socratic tradition, does that each day—one of many reasons why she loves him. His conscience is not so much pure as stalwart and restless. Like Jaspers, he grasps how much philosophy’s posing of questions can matter. People need philosophy, its rigor and scope, but they don’t know they need it.

Sometimes as she sat in that courtroom in Jerusalem she felt that she would explode with irony—a terrible feeling. The man in the dock was, as Americans put it, “a loser.” He could not think; he could only follow directions or register his displeasure with those who didn’t follow directions. He was not the person who should have been sitting there. Despite all the deaths he had orchestrated she felt that he was not the main act but an afterward. The horrific inspiration the Germans had derived did not emanate from this man who seemed in his vacant, responsible way nothing so much as narrowly ambitious. The enormous effort of the trial was spent on a hateful nothing.

But no—the trial (and she can’t help but think of Kafka) showed what the word conscience could be. In that sense those who excoriated her were wrong-headed. To live in a world without conscience was unbearable. To say that one conscience equaled another was foolish. As Eichmann showed too well, one conscience did not equal another. The scales were broken. Or they never worked to begin with. Kafka would have understood.

To say, “This is wrong” is as crucial as anything a human being can do. She gave examples in Eichmann in Jerusalem of people who paid with their lives for having a conscience. It was not complicated: the Third Reich was a nightmare they had to oppose. And yet she understands how easy rationalizing can be. Life is an extenuating habit. One Jew tells another Jew that things will be okay. Not all the rumors are bad. One Nazi tells another Nazi that a job must be done. There is honor. There is duty. There is the Fatherland. There is the Special German Way. Each abstraction is palpable. One German tells another German that the Führerknows what he is doing. “He has a plan.” She thinks of the story about the German woman at the end of the war saying, “The Russians will never get us. The Führer will never permit it. Much sooner he will gas us.” To which Hannah added: “There should have been one more voice, preferably a female one, which, sighing heavily, replied: And now all that good, expensive gas has been wasted on the Jews!”

She is clear about being a Jew first and last but the identity doesn’t buoy her. What buoys her is the patient, and, more likely than not, irritating quest for the truth of any small or large matter. What buoys her are the crowded streets of New York where people jostle each other, exchange greetings, gossip, wrangle, and mutter to themselves in various languages. The republic has no great task. Or its great task is to respect each person walking along Broadway, which is up to each citizen who constitutes the republic.

Like more than a few of her Jewish brethren, Hannah could have had a career as a comic or a writer of what has been called “black humor.” It comes with the burdensome territory inhabited by Job and Abraham and Sarah and Rachel, but she refuses to stay in that territory, much less indulge it. She is clear about being a Jew first and last but the identity doesn’t buoy her. What buoys her is the patient, and, more likely than not, irritating quest for the truth of any small or large matter. What buoys her are the crowded streets of New York where people jostle each other, exchange greetings, gossip, wrangle, and mutter to themselves in various languages. The republic has no great task. Or its great task is to respect each person walking along Broadway, which is up to each citizen who constitutes the republic.

Again, she stands outside a record store and listens. Some young men with British voices are shout-singing about love. “Help!” Sweet yet ardent, the word throbs with imploring warmth. She nods as if to acknowledge this most basic of human pleas. Something always is rising from the demiurge’s ashes. You wouldn’t want to live forever—but you would.

Baron Wormser is the author of many books. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. From 2000 to 2005 he served as poet laureate of the State of Maine. His essays have twice been included in Best American Essays and have appeared numerous times on Vox Populi. He has taught extensively as a freelance teacher and as a faculty member of three MFA programs.

Thank you so much for sharing this extraordinary essay by Baron Wormser that breathes, dances, grieves, and questions somehow, miraculously, from within the extraordinary mind, heart, and body of Hannah Arendt. It's a must read for the ages, and especially today, the anniversary of Arendt's death in 1975 in her New York City apartment at the age of 69. A Jew who fled Nazi Germany when she was 27 and became a U.S. citizen in 1951, Arendt saw America as the last best hope for humanity in an age of genocide when the “banality of evil” often goes undetected until it is too late. Her words, and Wormser's essay, have new meaning in our brave, new America. Once again, thank you Best American Essays for sharing it with the world.