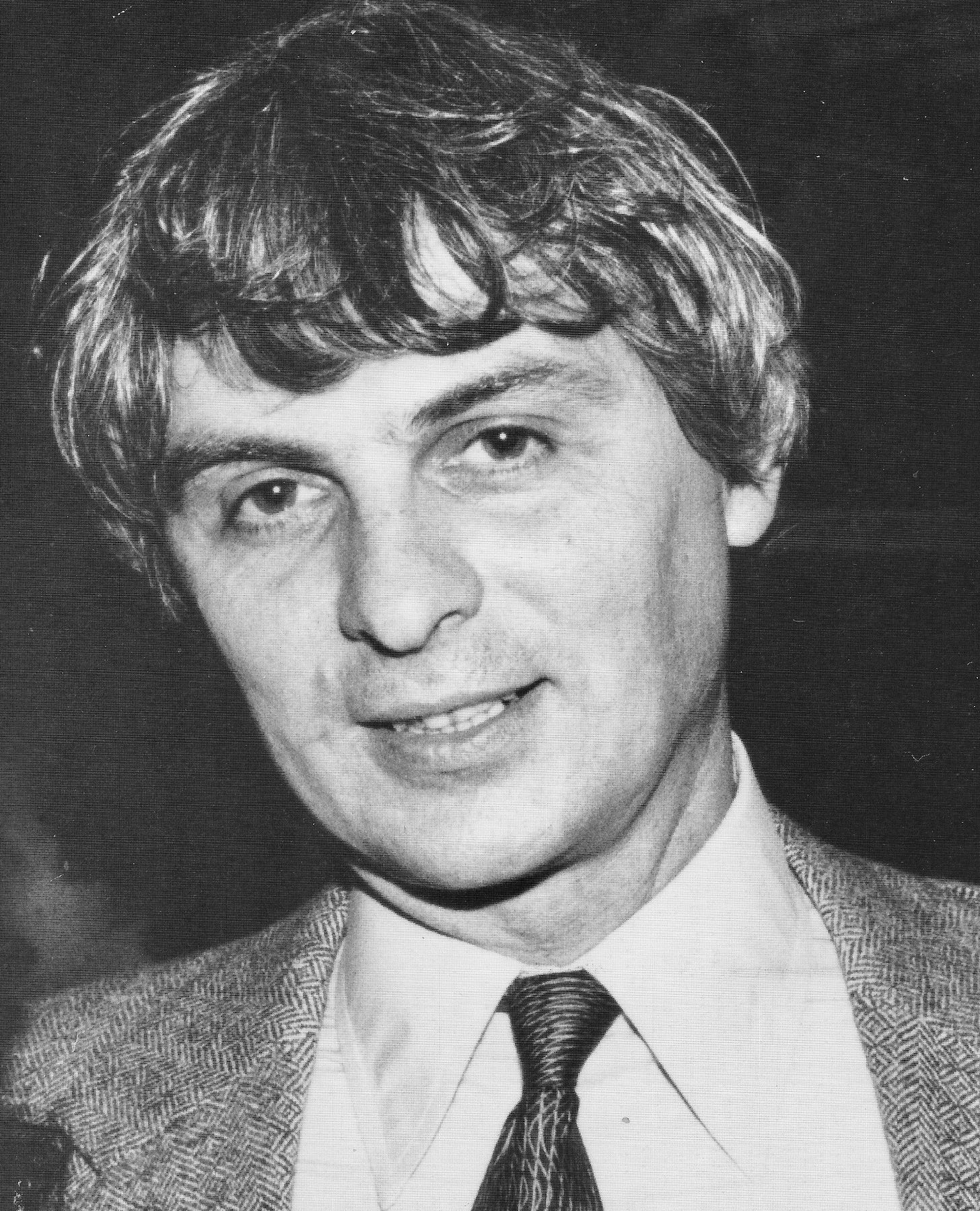

Today, the Best American Essays newsletter celebrates the eighty-fourth birthday of Robert Atwan, the founding series editor of The Best American Essays.

Born and raised in Paterson, New Jersey, Atwan was the eldest child in a first-generation, working-class family and the first to complete high school and attend college. After graduating from Seton Hall University, he pursued graduate study at Rutgers University, where his mentor was the outstanding critic Richard Poirier. He began his career as a freelance writer and independent scholar in 1974 with a focus on American literature and popular culture. In 1978, he worked at the Ford Foundation to coordinate and prepare the proposal that would become the celebrated Library of America.

In 1985, Atwan founded The Best American Essays series, which he edited for thirty-eight years until he retired in 2023. He has published numerous anthologies, along with essays and reviews on a wide range of topics that include dreams and divination in ancient literature, American advertising history, Shakespeare, censorship, essays and essayists, memoir and creative nonfiction, sports, cinema, and photography. In retirement, Atwan is slowly gathering scattered old and new writing together in one place. It is still a work-in-progress. Readers will find a handful of stories and a forthcoming novel at a quirky new Substack journal The Hodge Review.

For a wonderful biographical essay curated from Atwan’s forewords, see Nicole Wallack’s “Robert Atwan’s Art of the Foreword,” in Essay Daily, December 2015.

Subscribe to our newsletter for news about upcoming online conversations with Best American Essays contributors about essayists.

Confessions of an Anthologist (from The Best American Essays 2011)

While speaking at a panel devoted to the essay a few years ago, I was surprised to be introduced as one of America's noted anthologists. No one had ever called me that before, nor had I ever thought of myself that way, but afterward I began to reflect on the unusual compliment, which I assume it was.

I had never considered anthologizing as a special talent, but, I admit, I have compiled quite a few. Not just [The Best American Essays]—but numerous collections of short stories, poems, political and cultural commentary, memoirs of movie stars, even historical advertisements. Had my early submissions of poems and stories met with more receptivity or had my first publication, a 1973 college anthology called Popular Writing in America (the title is still in print), which I coedited with a very good friend, Don McQuade, not been a success, I may not have risen to the esteemed rank of a "noted anthologist." But in publishing (as in so many industries) a success in one endeavor is often followed by an invitation to do something similar, and so one anthology followed another, but not always successfully.

I'm certain that no one ever set out to be an anthologist. It is hardly a conventional career path. “What would you like to be when you grow up, kid?” “That's easy, sir—a noted anthologist.” But I did possess the one important characteristic that qualified me for the job. As far back as first grade, I enjoyed reading anything and everything. I even loved to read the required Baltimore catechism with its endlessly fascinating questions— “Why did God make us?”—and all the textbooks the good sisters passed out to us on the first day of every school year. On the opening day of third grade I brought our reader home and finished it that night. Given the typeface and all the illustrations, it was hardly a challenge; I would realize in time that as the books got harder, the print got smaller.

I was not just a voracious and indiscriminating reader, I was an obsessive one. This sometimes worried my father, who never read anything other than the New York tabloids and daily racing sheets, which of course I devoured as well once he was done. He was concerned that a kid who always had “his nose in a book” would grow up unfit for the rough-and-tumble conditions of our sketchy environment. So I reduced his worries by playing baseball, though there were many times while standing alone out in center field inning after inning waiting for a fly ball that I wished I had hidden a Zane Grey paperback inside my perfectly oiled Rawlings.

I'm not usually sold on epiphanies, especially of the life-transforming type. I'm more interested in the opposite experience: not those rare moments of startling insight or realization, but—what I suspect are more common—those sudden flashes of anxious confusion and bewilderment. I distinctly recall experiencing one of these reverse epiphanies (is there a word for these?) shortly after I began high school. Before then I had been a regular visitor to our cozy, storefront branch library, where I borrowed book after book, usually biographies of Hall of Fame baseball stars, all through the summer months. But during the first week at St. Joseph's High School, one of the nuns suggested we obtain a card from the main branch of the Paterson Free Public Library. I had never set foot inside this imposing building with its stately columns that looked a little like the Lincoln Memorial (and no wonder—the same architect, I would later learn, had designed both). I entered the expansive lobby with some trepidation, not yet feeling a sense of belonging; libraries had not yet become the convivial community centers they are today. Libraries then were all about books, and librarians were the stern guardians of those books. An intimidating decorum of absolute silence prevailed as I timidly glanced about, astonished to find more books in one place than I had ever pictured, awed by the gleaming mahogany card catalogues that looked longer than the Eric Railway boxcars that click-clacked by our house hour after hour. As I walked out past the columns and cautiously down the steps, now a card-carrying member of this humbling institution (and, by some sort of worrisome magical extension, an adult), I rejoiced that with so much available to read, I would never be bored in my entire life. And yet with a dizzying sense of unease, I simultaneously felt a terrifying rush of unknown possibilities.

The word anthology derives from the Greek antholegein, which literally means to gather (legein) flowers (anthos). The anthologist in a sense gathers a literary bouquet. Or as the founding father of all anthologies, Meleager of Gadara (now the city of Umm Qais), and apparently my ancient countryman, called his first-century BC compilation of short verse, a garland. Despite its unusual etymology, one that very few readers probably know, the anthology has remained a popular publishing product for over two millennia. So we anthologists possess a long literary tradition, though I know of no history that charts our endeavors or the progress of Meleager's Garland into the Norton Anthology of Poetry.

The first anthology I remember owning was Oscar Williams's Pocket Book of Modern Verse. I acquired this while a high school senior and read it for years until it finally fell to pieces. Williams became one of the nation's most influential promoters of poetry, and his inexpensive paperback collections could be found in the 1950s and '60s in every bookshop, on drugstore racks, and in countless college classrooms. They are still being sold on Amazon.com, to the accompaniment of many warm and nostalgic reviews, a few of which informed me that my copy was not the only one read to pieces. Any history of the modern anthology would need to include Oscar Williams, a Ukrainian Jewish immigrant, born Oscar Kaplan. Williams was also a poet about whom Robert Lowell wrote, “Mr. Williams is probably the best anthologist in America today.”

Although The Pocket Book of Modern Verse was well thumbed and well loved by thousands of readers, it did not approximate the literary impact of Harriet Monroe's famous 1917 collection, The New Poetry: An Anthology. That authoritative book proved to the public that something indeed had happened to poetry around the start of the century's second decade. Monroe's collection was the literary equivalent of the groundbreaking 1913 Armory Show, a visual “anthology” that mapped the enormous changes occurring in the world of art. By gathering a large sampling of the emerging poets of her time, Monroe (who included a dozen of her own poems) was able to demonstrate—as no single collection by an individual poet could—that a distinct movement was afoot and that modern readers had better start to swim with Ezra Pound rather than sink with Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

I've mentioned two influential poetry anthologies and I could mention others. Poetry movements have often been accompanied by anthologies that serve as manifestoes. But what about essays? Although there have been a number of excellent essay collections, mostly with a historical sweep—the best of which is Phillip Lopate's comprehensive and indispensable The Art of the Personal Essay (1994)—I can think of no dedicated, single-volume, twentieth-century essay anthology that did for the modern essay what Harriet Monroe's book did for modern poetry. That might be because the essay was so slow in coming to terms with modernism: as I've written before, the essay, with very few exceptions, was the vehicle for understanding modernist literature, not a key part of that literature. Perhaps the most important anthology to showcase essays with a new voice and edge was Alain Locke's 1925 landmark collection, The New Negro: An Interpretation, which served as the major statement of the Harlem Renaissance. Though multigenre, the collection featured a preponderance of essays that clearly disassociated the form from the popular genteel essay and positioned it solidly in the new century. Another collection that would give voice to a new movement, not essayistic yet closely related, was Tom Wolfe's and E. W. Johnson's The New Journalism, the 1973 manifesto/anthology which celebrated a new style of nonfiction prose that had grown out of the ashes of the finally deceased novel.

But unlike The New Poetry or The New Journalism, there was no twentieth-century anthology entitled The New Essay, no gathering of key selections from a single period that demonstrated a vital literary movement gaining momentum. But as the twenty-first century opened, one young essayist, John D'Agata, noticed a new, hard-to-label form of essayistic prose that didn't resemble the traditional personal essay or nonfiction narrative or literary journalism, He collected these in a 2003 anthology that he called The Next American Essay. To be sure, some of these essays went back a few decades (such as John McPhee's brilliant 1975 New Yorker piece "The Search for Marvin Gardens"), but all the selections had something in common: a determination by their authors to push the genre into new territory, to feature prose that—to put it quickly—depends more on poetic fragmentation than rhetorical coherence and discontinuous narrative than straightforward self-presentation. The trick, of course, is to employ innovative forms without sacrificing ideas, substance, or urgency.

—Robert Atwan

“What prevents personal writing from deteriorating into narcissism and self-absorption? This is a question anyone setting out to writer personally must face sooner or later. I’d say it requires a healthy regimen of self-skepticism and a respect for uncertainty. Though the first-person singular may abound, it’s a richly complex and mutable I, never one that designates a reliably known entity. One might ultimately discover, as […] Diane Ackerman [puts it], ‘a community of previous selves.’ In some of the best memoirs and personal essays, the writers are mysteries to themselves and the work evolves into an enactment of surprise and self-discovery. […] Surprise is what keeps ‘life writing’ live writing. And, finally […], there must be […] resonance—a deep and vibrant connection with an audience. The mysterious I converses with an equally mysterious I.”

“By temperament, the essayist doesn’t favor the final word but prefers to remain in an exploratory frame of mind. Essayists like to examine—or, to use an essayist’s favorite term, consider—topics from various perspectives. To consider is not necessarily to conclude; the essayist delights in a suspension of judgment and even an inconsistency that usually annoys the ‘so what’s your point’ reader. The essayist, by and large, agrees with Robert Frost that thinking and voting are two different acts.”

First published essay:

“Newspapers and the Foundations of Modern Advertising,” in The Commercial Connection: Advertising & the American Mass Media, edited by John W. Wright (Delta, 1979).

Selected essays on the essay and essayists:

“Ecstasy & Eloquence: The Method of Emerson's Essays” in Essays on the Essay: Redefining the Genre, edited by Alexander Butrym (University of Georgia Press,1989).

“...Observing a Spear of Summer Grass,” The Kenyon Review, Spring 1990.

“The Essay—Is It Literature?” in What Do I Know: Reading, Writing, and Teaching the Essay, edited by Janis Forman (Boynton/Cook, 1995); reprinted in Essaying the Essay, edited by David Lazar (Welcome Table Press, 2014).

“E. B. White: A Note on ‘The Death of a Pig’,” Creative Nonfiction, Spring 2011.

“Notes Towards the Definition of an Essay,” River Teeth, Fall 2012.

“The Assault on Prose: John Crowe Ransom, New Criticism, and the Status of the Essay,” in How We Speak to One Another, edited by Ander Monson and Craig Reinhold (Coffee House Press, 2017).

“Of Sex, Embarrassment, and the Miseries of Old Age [after ‘On Some Verses of Virgil’], in After Montaigne: Contemporary Essayists Cover the Essays, edited by David Lazar and Patrick Madden (University of Georgia Press, 2015).

“Prologue: How Nonfiction Finally Achieved Literary Status,” introduction to I’ll Tell You Mine: Thirty Years of Essays from the Iowa Review Nonfiction Writing Program, edited by Hope Edelman and Robin Hemley (University of Chicago Press, 2015).

Readers interested in the origins of The Best American Essays series might be interested in “The Best American Essays: Some Notes on the Series, Its Background and Origins,” in Essay Daily, December 7, 2015.

See also:

Nicole Wallack, Crafting Presence: The American Essay and the Future of Writing Studies, Utah State University Press (2017).

Ander Monson, “On Finding The Best American Essays 1999 at the Bear Canyon Goodwill,” Essay Daily, December 2015.

Robert Atwan Interviewed by Karen Babine in Assay: A Journal of Nonfiction Studies